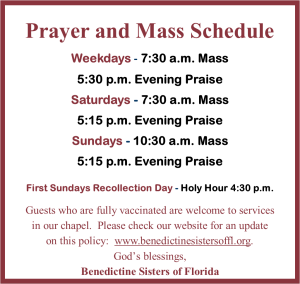

This Gospel is a very familiar incident in the life of Jesus – many reflections have been written about it – so, today I offer you a different perspective on the occasion … this one was related to me by Claudia, the wife of Pilate [adapted]

This Gospel is a very familiar incident in the life of Jesus – many reflections have been written about it – so, today I offer you a different perspective on the occasion … this one was related to me by Claudia, the wife of Pilate [adapted]

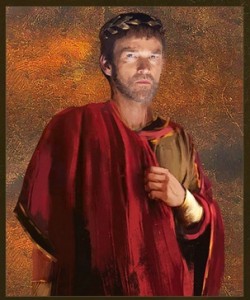

I wonder sometimes, if they might have been friends this Jesus and my husband Pilate. If they had met in some other circumstances, I think they might have liked each other. Afterall, they were about the same age. They were both passionate, committed, opinionated. Bullheaded sometimes. And intelligent too. Except they thought so differently. Jesus was a Jew. Pilate was a Roman. And Pilate never understood the Jews. “You can’t get a clear answer out of them about anything,” he would fume. “Ask them a straight, logical question and they tell you a story or sing you a song!”

Pilate knew perfectly well he would never have gotten the appointment as Governor if he hadn’t been married to me, the granddaughter of the Emperor Augustus. And even at that, Judea wasn’t exactly a plum of an appointment. But Pilate hoped that his next appointment would be more prestige, a little closer to Rome; something he and I would both be proud of.

But in Judea things had gotten off to a bad start – he’d had a showdown with the Jewish leaders over whether Caesar’s image could be displayed in the temple area. It was a dumb thing to fight about and Pilate knew it. “But I’ve got to show them I am strong and resolute, Claudia,” he said to me. “If I show just a hint of weakness, if I back down even an inch, that snake of a high priest, Caiaphas, will take every slight advantage that I give him.”

Judea was a ‘no-win’ situation for him. The bureaucrats in Rome just read the bottom line. Did he collect his quota in taxes? Did he avoid any embarrassments? If the answer was “yes” to those questions, you stayed on and maybe eventually got promoted to a better posting. If “no” you were recalled to Rome and sent to shuffle papers in an office somewhere. Judea was so much more complicated than they realized.

Pilate tried. How he tried! He read that blessed policy manual every night and memorized every procedure. But of course the manual procedures never fit reality. “Who wrote this stuff anyway,” he fumed. “I bet they’ve never been outside of Rome. They sure as the dickens have never been out here in the boonies of Judea.”

And then the Jesus business broke. It was a recipe for disaster. Pilate couldn’t win this one and I knew it and I think he knew it. I even had dreams about it. “Get this man Jesus out of your life, Pilate,” I said, “No matter what you do, you’ll lose,” “I’ll do what’s appropriate and necessary, Claudia,” Pilate said in his official voice, which meant that he was frightened. “I will interview the prisoner and judge him according to our Roman justice. He will be treated fairly.” And there the conversation ended.

When they brought the prisoner up to the Prætorium. Pilate met them outside, a gesture of good will. He interviewed Jesus there in front of the Jewish leaders. “Look,” he finally said. “the guy is just a little crazy, and yes, a bit of a trouble-maker. But he hasn’t done anything to deserve execution. I mean, I can’t have him killed just because you people don’t like him. What I’ll do is have him flogged. That’ll straighten him out.” Well, you should have heard the hullabaloo. “We want him dead!” they yelled. “Give us Barabus! We want him crucified!”

Listen. My husband has integrity. He wasn’t about to execute a man unless a crime had been committed, and blasphemy against the Hebrew God was no crime in Roman eyes. But Pilate was no fool either. He knew that Caiaphas had his ways of getting messages to Rome. What followed was a mish-mash of political maneuvering and charges and counter charges. I don’t quite know what happened. I was in bed for most of it, fighting one of my migraines.

But I won’t not soon forget what happened when Pilate dragged this Jesus up into our quarters, away from all the yelling and screaming outside. That was when it struck me how alike they were, and yet how different. Two men of talent and integrity speaking to each across such vastly different realities.

In spite of all the pressure, Pilate still wanted to do the right thing. “Look,” he said to Jesus. “Give me a reason, give me something, anything that’ll satisfy that mob–something I can put in my report to Rome so I don’t have to have you killed.” Jesus looked right back at Pilate–looked through him. But he said nothing.

Pilate lost his cool. “Look, don’t you know I have the power of life and death over you. I can send you out to be torn apart by that mob, or I can save your hide.” “You have no real power over me,” said Jesus. “No power that really counts. You and I are caught in this evil drama. You have your role to play and I have mine. “All right,” said Pilate. “What is your role except to satisfy the blood-lust of that mob?” “I am called to live the truth,” said Jesus. “What is truth?” Pilate asked quietly, almost cynically. Jesus looked at him intently. And yes, compassionately. But he said nothing. “Look, I asked you a question. What is truth?” Pilate lost his cool again. He paced around the room and banged his fist against the wall. But both men knew, I think, that Jesus could not reply in any way that Pilate could comprehend.

The conversation stopped. There was nothing else to say. Jesus would die. And Pilate knew he’d spend the rest of his life rehearsing that conversation. “Why couldn’t he just explain to me, logically and rationally what he was up to?” Pilate asked that question over and over.

I too have rehearsed that conversation. I am back in Rome now, by myself. Pilate has been banished from the capitol. Pilate did not understand Jesus or any of the Jews.

And yet I wonder: If Pilate and this Jesus had met some other way, perhaps they would have learned to like each other – if they had a chance to really talk, without the pressure. Pilate, the logical philosopher might have discovered the poetic dreamer deep inside himself. And Jesus the poetic dreamer, might have shown to Pilate the philosophy on which his dream was built. There would have been respect at least. And just perhaps they might have seen themselves as brothers.